The UK has surged ahead in the race to harness power from the oceans, with its tidal energy sector now dominating global project pipelines.

A new report by the Energy Industries Council (EIC), the world leading trade association for the energy industry’s supply chain, reveals the country accounts for nearly 40% of all wave and tidal projects worldwide, making the country a testing ground for technologies that could reshape renewable energy markets.

“The UK’s Contracts for Difference scheme has been a game-changer,” said Nabil Ahmed, author of the EIC report. “By ring-fencing funds specifically for tidal energy, the government has given developers the confidence to scale up.”

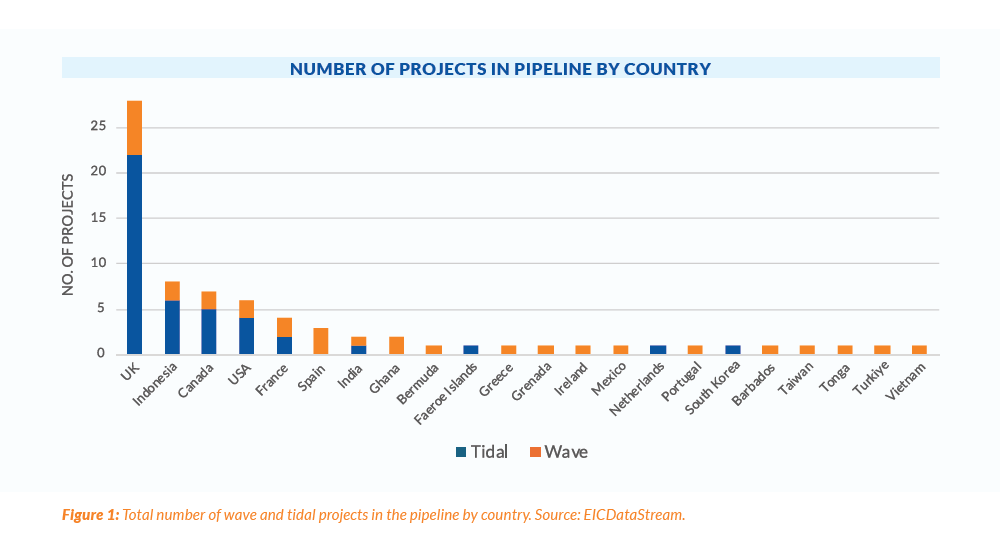

The numbers speak for themselves. Of the 74 wave and tidal projects EIC databases track globally, 28 are in the UK, 22 tidal and 6 wave. Scotland alone is home to 14 projects, including the MeyGen tidal array, set to become the world’s largest at 398 MW. The UK’s tidal pipeline has already secured £45 million in government support across three CfD auction rounds, with strike prices falling from £178.54/MWh in 2022 to £172/MWh in 2024.

“Tidal’s predictability gives it an edge over wind and solar,” said Ahmed. “The UK’s focus here isn’t just about hitting net-zero targets. It’s about building an exportable industry. The expertise gained in the Orkney Islands or the Bay of Fundy could be sold to coastal nations worldwide.”

The sector’s Achilles’ heel remains cost, globally. Tidal stream projects in the UK still require subsidies of £172/MWh, which is triple the current wholesale power price. Wave energy is even pricier, with no projects yet winning CfD auctions.

“Costs will fall as technology scales,” Ahmed said. “Tidal has already dropped 30% in a decade. The goal is to hit £100/MWh by 2030. That’s when you’ll see banks and pension funds jumping in.”

Across the Channel, the EU is making its own push. The bloc’s Horizon Europe program has earmarked €95.5 billion for green energy research and development, with marine projects like France’s 17.5 MW Flowatt tidal farm and Portugal’s 20 MW wave energy site competing for funds. Europe’s pipeline includes 13 projects, though it lags behind the UK in both scale and policy clarity.

“The EU’s 1 GW target for ocean energy by 2030 is achievable, but only if member states align their incentives,” Ahmed said. “France and Portugal are leading, but others need to catch up.”

Half a world away, Indonesia is waking up to its marine energy potential. The archipelago nation has the largest project pipeline in the Asia-Pacific region, with nine wave and tidal developments underway. Projects like the 150 MW Nautilus Tidal Power Project aim to tap into an estimated 63 GW of marine energy resources, enough to power the country twice over.

“Indonesia’s challenge isn’t resources, it’s regulation,” Ahmed noted. “Overlapping agencies and a lack of feed-in tariffs have slowed progress. But if they get the policy framework right, this could be a $20 billion market by 2040.”

The U.S. and Canada, despite vast coastlines, trail behind. The U.S. has six projects in development, including the PacWave South test site in Oregon, while Canada’s seven projects focus on Nova Scotia’s Bay of Fundy, home to the world’s highest tides. Combined, their pipelines total just 68 MW, a fraction of the UK’s recommended 300 MW target for 2030.

“North America has the resources but not the urgency,” Ahmed said. “The U.S. Department of Energy’s $18 million R&D commitment is a start, but they’ll need CfD-style revenue guarantees to attract serious private investment.”

Global installed capacity could reach 300 GW by 2050, per IEA estimates, with a market value of $340 billion. But getting there will require more than just optimism. “Governments need to stop treating marine energy as a science project,” Ahmed said. “The UK’s CfD model works because it treats tidal like a mainstream renewable. Others need to follow or get left behind. For now, all eyes are on the UK’s next CfD auction in 2025. If the ring-fenced tidal budget grows, as industry advocates demand, the country could solidify its lead—and prove that the oceans’ power is more than a drop in the renewable energy bucket.”